From the Magazine

Mouchette: Two Deaths

Returning to the scene of Robert Bresson’s 1967 classic of childhood despair.

Share:

This essay appears in Issue 1 of The Metrograph, our award-winning print publication. Explore more of Issue 1 and newer editions here.

CHILDHOOD IS A BLEAK COUNTRY. The inexplicable and the unreasonable rule the land. Children, even the lucky ones, live at other people’s mercy, though who those other people are is a forbidden question. This, if you think about it, must be one of the secrets that most adults conspire to keep from the children. The parents, teachers, and caretakers who dictate how our days should go—they, too, live at other people’s mercy, and they don’t always want us to know it. Childhood is a happy time, a carefree era, a golden age: how else can such a false myth be perpetuated if not for the collective effort of the adults? Many children, once entering adulthood, participate in such a make-believe. Perhaps people are forgetful.

I came across Robert Bresson’s film Mouchette (1967) in a roundabout way. I was working on a novel set in rural France in the 1940s. I did not grow up in postwar France, though that did not particularly worry me. My grandfather was an illiterate peasant in an extremely impoverished region in South China; my father, a nuclear physicist, settled us in a research institute in Beijing, which back in the 1970s was surrounded by farms. Countryside, with the many sounds and smells of bullied and butchered lives, with the seasons and weathers indifferent to the meager wishes of the poor, is the same countryside no matter where it is located. Countryside is as universal as childhood.

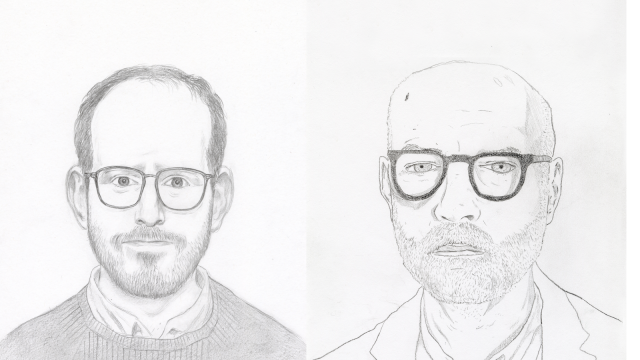

Still, I asked my friend Edmund White for some recommendations of books set in the French countryside, and he suggested Georges Bernanos’s work. Bernanos (1888–1948) spent his childhood in a village in the Pas-de-Calais region, which became the frequent setting of his novels, including The Diary of a Country Priest, Under the Sun of Satan, and Mouchette. I read the three books as part of my research, but Mouchette continued to haunt me long after my research was finished, and long after my own novel The Book of Goose was published.

Mouchette, a short novel, or a novella (141 pages in the French edition I read, 127 pages in J.C. Whitehouse’s English translation), covers the last 24 hours of a 14-year-old girl’s life. Mouchette (“little fly”), born to alcoholic parents in a poor village, is a social outcast. Her school mistresses and schoolmates treat her as a nuisance and an idiot, the villagers call her a liar and a savage, and her own parents have little affection for her. “Tragic solitude,” as Bernanos remarks in the preface to the novel, is the essence of her being. It is the state in which she lives and in which she also dies.

The film Mouchette, based on the Bernanos novel, is one of Bresson’s best films, and is often considered one of the greatest films in history. The film, no longer confined by the 24-hour time frame of the novel, has added contemporary touches: a bumper car ride, for instance, becomes one of the few bright moments in the on-screen life of Mouchette. And yet, despite the different period details, both the novel and the film are timeless: the countryside is the countryside no matter what year the calendar says; childhood is still that bleak country, and still there is no escape.

Mouchette (1967)

There is one major difference between the last scene of the novel and that of the film. In the novel, Mouchette—neglected, bullied, violated, humiliated, unloved, uncared for—walks around in the village like a ghost. An old woman, seeing her clothes sullied and torn after a rape, gives her some clothes from her own youth. Mouchette carries the parcel and wanders to an abandoned quarry, where “the water was so clear that no fish would live there.” There, she ponders life and death, makes a half-hearted attempt to draw a passerby’s attention to her despair (“She would have liked to shout, call out, and run out to meet her grotesque saviour; he plodded slowly on his way and suddenly seemed to be disappearing”), then drowns herself.

The final paragraph of the novel goes like this:

Mouchette slid down the bank until she felt the gentle sting of the cold water on her leg and as far as her thigh. The sudden silence inside her seemed infinite, like that of the crowd as it holds its breath when the trapeze-artist reaches the top rung of the ladder. Her will dissolved. She slid out into the water, pushing against the bank with one of her hands. She could hold herself up in the shallow water by the pressure of one hand on the bottom. Then she twisted over and looked up into the sky. She felt the insidious flow of the water along her head and neck, filling her ears with its joyful sound. She knew that life was slipping away from her, and the smell of the grave itself rose to her nostrils.

This last moment of a dirt-poor Ophelia may be my only quibble with the novel: the exit from that bleak country called childhood, or life, is made too easy and too lyrical here. In this way Mouchette’s death has entered realms mythological, religious, and spiritual. The novel, harrowing, harsh, ends on an almost comforting note, as if it aims to settle rather than to unsettle—perhaps only a gesture.

The final scene of the film, which lasts about three minutes, provides a variation that is much less consoling, even though it has retained, on the surface, the same mood of serenity. Mouchette, played by Nadine Nortier (in her only film performance), opens the parcel on the bank of the quarry and studies the clothes given to her by the old village woman, including a white dress, better than anything she has seen. She measures the dress, which is a little large, against her body, but instantly the hem is caught by a thorny branch. She pulls, and the dress tears.

What Bresson captures here (as elsewhere in the film) is the slowness of Mouchette, whose every facial expression and every gesture bears the seriousness and the difficulty of being a child: thoughts and feelings, having not yet found ways to articulate themselves through language, become a physical burden.

Instead of putting on the dress, Mouchette wraps it around herself—we can feel the exhaustion and despair in that moment: putting on a dress properly is beyond her, just as any kind of life is beyond her by then. She then rolls down the slope, over the uneven ground, only to lose momentum when she is only halfway to the water.

A church bell tolls. A tractor is heard to be driving past. Mouchette sits up and raises a hand at the tractor driver, one of the few gestures in the film when she tries to connect to another human being. The man looks back briefly, incuriously, and drives on, vanishing into the field of high grasses.

Mouchette goes back up the slope and again wraps the dress, now more torn, around herself. The church bell continues to toll. She rolls down a second time, more resolute, but still she fails to die. She is stopped next to the water by some meager bushes. And so she walks up one more time and rolls down one more time, and it is the third time that brings her luck: the girl disappears into the water, and the dress, a pile of torn fabric, hangs on among the bushes. There is no underwater twisting in which the girl turns to face the sky, nor is there the indication that the water is shallow and she can hoist herself easily out of death. It is deep water under the sun, without even a bubble bursting at the surface. Then the music starts, a tune played on two oboes, joined by human chanting.

Here is a death that continues to haunt long after the film ends. Here, unlike in the novel, death grants no mystic or religious power. It only leaves an enduring bafflement, which is like an enduring wound. That Mouchette has tried and failed to die the first two times: shouldn’t that be enough? Couldn’t the camera move to another scene, in which the girl resumes her life in her monumental solitude and misery? Here the death of a child does not come as the natural ending of a story, carrying the clear sign of “FIN.” Rather, it arrives as though mid-sentence. Somewhere a phone line gets disconnected without a warning. We dial back, and there is no one to pick up, so we cannot say to the child that we, too, dwelled in that bleak country of childhood once. But even if we could say that, what difference would it make? That some of us—many of us—have survived childhood does not mean all children survive.

I have watched the ending of the film many times, searching for the possibility of an alternative. But of course Mouchette dies, again and again, after she has tried and failed, again and again. And again the oboes come in, playing the music that is nearly tuneless. And again men start chanting, wordlessly.

(Perhaps I should have stated, at an earlier point, that my son Vincent also died from suicide, just a little older than Mouchette.)

(Or I could have added that he was once an oboist.)

(Or, regarding the torn fabric on screen, I could have relayed a story Vincent wrote at 14, about a young boy running away from the Russian Revolution with his mother and his nanny. They put a new jacket on him, and he cannot stop fingering the brass buttons: “Then a button came undone, and the coat was no longer new.”)

But these are parentheses. It is possible, at times, to put them outside what one cannot name, understand, or categorize: parentheses make a narrative manageable.

And yet that bleak country called childhood cannot be contained in parentheses. Life cannot be lived solely in parentheses. Outside the parentheses, one’s only hope is to stay baffled, which means to stay wounded, which means to decline the convenience of any easy closure. The two deaths of Mouchette at least give that solace: there is no closure here.

Share: