Columns

Cracked Actor: Romy Schneider

On the beauty and commanding presence of the actress in film and in life.

Ravishing Romy opens at Metrograph Theater from Saturday, September 6.

Share:

In a 2011 interview between the German fashion designer Karl Lagerfeld and former Vogue Paris editor Carine Roitfeld, the conversation turned to a patent leather coat in Claude Sautet’s 1971 film Max and the Junkmen, and Romy Schneider, the woman who wore it.

LAGERFELD: Romy was not very chic. She was an actress of genius, but that’s it. She had strange proportions. She was not that beautiful.

ROITFELD: But she had an exceptional face.

LAGERFELD: In movies. Not in life so much.

ROITFELD: Is it better to stay beautiful in the image or to be beautiful in life? That is the question.

All stars are beautiful. We take that for granted. Iconography is what’s slippery. Sublime physical beauty often obscures the force of the interior; that’s a magic trick. Schneider was already a major celebrity, fresh from working with Orson Welles and Otto Preminger, when Henri-Georges Clouzot cast her in Inferno. The psychosexual drama began filming in 1964, with Schneider as the wife of a man undone by lurid hallucinations of her infidelity. Despite the facile logline, Clouzot’s ambition, with hubristic technical scope, was to formulate an avant-garde language not yet seen in cinema. Black-and-white sequences would be intercut with disorienting visions of Schneider in psychotropic color and other optical distortions. To prepare, the Diabolique (1955) director and his cameramen spent months conducting a series of wardrobe tests, manipulating light and color projections, double exposures, and other abstractions. The shoot was its own kind of l’enfer; Clouzot had a heart attack during filming and ended the project. What survives, aside from a documentary on the failed production, is footage of Schneider, holding control of the image.

Schneider suffered from perfection. She was simply too good. And too beautiful. The misperceptions between appearances and the genius of the woman behind them is too common a story. The eroticism Schneider suffused in many of her roles was often a prelude, or a companion, to perfectly calibrated detonations of emotion. How she owned the camera so completely, in such an unassuming fashion, remains a mystery of her technique. In films like La Piscine (1969) and The Things of Life (1970), she is remembered for being, to Lagerfeld’s objection, “chic,” an ideal incarnation of the liberated bourgeois. Her death at age 43 made her a cult object of tragedy. All she wanted was credibility.

Clouzot’s screen tests dissolved the illusion of anything but Schneider’s intensity, capturing the planes of her feline face moving with the gravitas of a Silent star. In green and yellow chiaroscuro, exhaled cigarette smoke enters her mouth in reverse; her eyes flicker open under heavy mascara in extreme black-and-white close-up—her skin, alien, flecked with glitter. Exquisite scenarios alternate with the sordid. One features Schneider lit in multicolor and smiling slowly, her head enveloped in cellophane with a big pink bow tied around her neck, a pert floral bouquet waiting for delivery. Two hands reach out of the void to encircle her throat, strangling her.

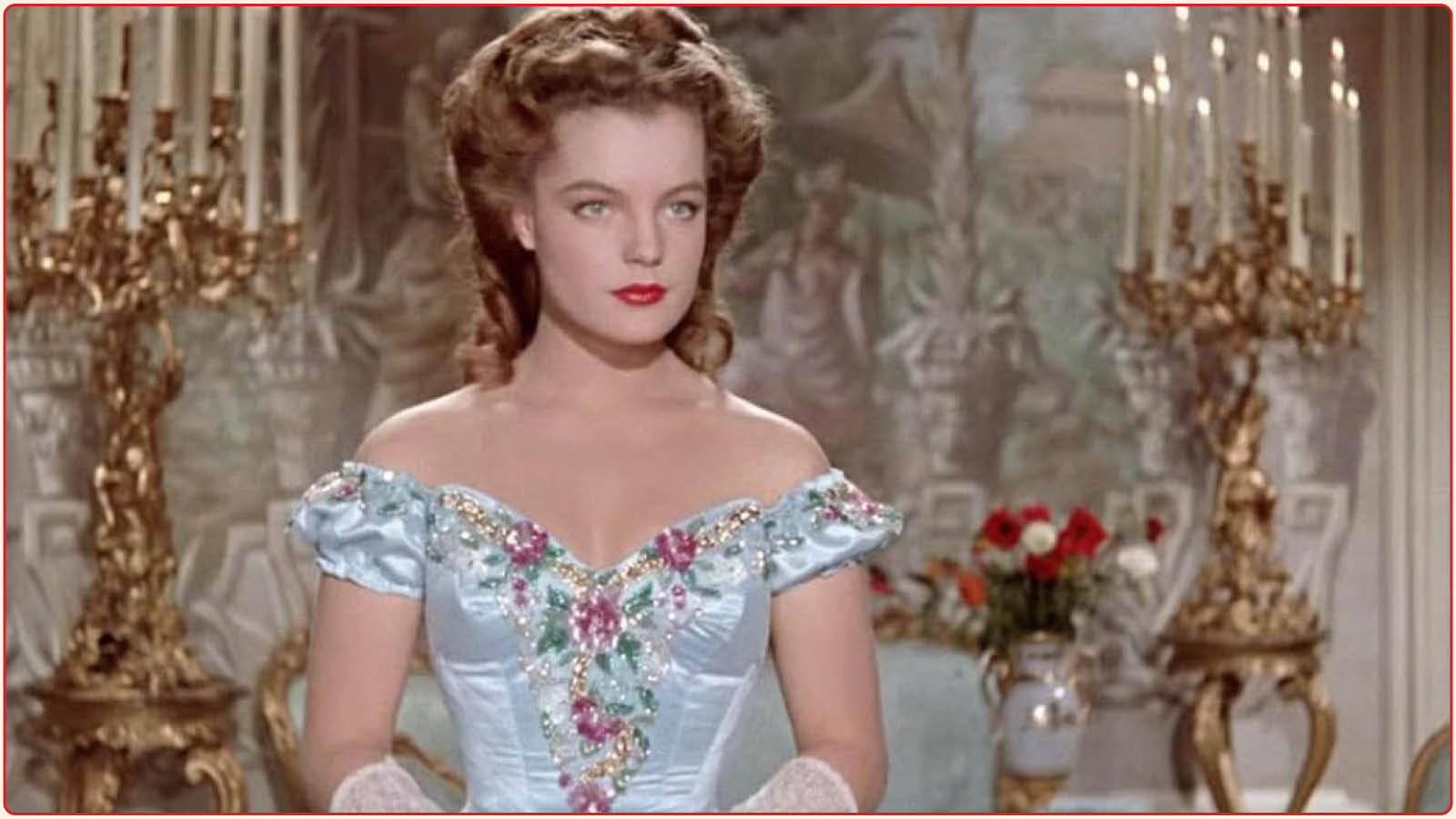

Sissi (1955)

Schneider’s mythology starts in Vienna, 1938, months after the Nazi annexation of Austria. Her parents, both actors, were Nazi sympathizers. Schneider and her brother were raised by their grandparents in Bavaria before she was sent to boarding school at age 10. Famous by 17 for playing the tomboyish teenage Empress Elisabeth of Austria in Sissi (1955) alongside her mother, Schneider spent much of her later life grappling with the legacy of both her parents and her country. (In the ’70s and ’80s, Schneider actively sought roles in films like The Train (1973) and The Passerby (1982), about persecution under the German Occupation, an artistic avenue for her antifascist politics.) Sissi was a well-matched vehicle for the young actor’s effervescence: the princess first springs into frame on horseback, jumping over a bed of roses. But the eventual trilogy, mannered waltzes animated by meringue-like crinolines and saccharine romance, was a confection of Habsburg nostalgia that clouded Austria’s recent fascist reality.

Sissi would define Schneider in the way that first impressions reduce a subject to its contours. Seeking new material, she refused to participate in a fourth film, but reprised the character years later in Luchino Visconti’s Ludwig (1973). The director became an influential collaborator for Schneider early in her career. She dedicated her 1976 César win, for Andrzej Żuławski’s That Most Important Thing: Love (1975), to him: an homage to a man who saw the sinew behind the princess. The last film in his “German Trilogy” after The Damned (1969) and Death in Venice (1971), Ludwig, an epic of the decadence and madness of King Ludwig II (Helmut Berger), is the culmination of Visconti’s compulsion for the baroque. The Milanese prince had a taste for laying bare the vaunted classes’ inner rot, and the Sissi of Ludwig exhibits a sly metatextuality carefully deployed by Visconti and Schneider. To consider both Sissis side-by-side is startling. They cannot be mirrors, and instead are a portal: the future Schneider uses her fully realized sophistication to recontextualize the past. Again, the Empress is recognizable by meters of luxurious curled hair (the actual woman was said to wash with raw eggs and cognac) and first appears on a horse, but this time she’s trotting under a circus tent in a ring lit by a single spotlight. Her comportment is imperious, controlled, fetishistic. She advises her cousin, newly ascended to the throne, “We are just a façade, we are easily forgotten. Unless they give us a bit of fame by killing us.”

In one scene, Schneider, veiled in black dotted Swiss, surveys the expanse of an ostentatiously gilded hall of another vacant fairy-tale castle Ludwig has constructed. Well advanced into decay, he has refused to see her. Her laughter rings out, echoing cruelly, both judgement and verdict. The real Sissi was assassinated by an Italian anarchist as she prepared to board a boat headed from Geneva to Montreux in 1898. He concealed a needle file behind a bouquet of flowers before puncturing her in the heart. The Empress’s tightly-tied corset initially staunched the bleeding, but she collapsed, dying less than an hour later. Schneider never portrayed that onscreen.

Sissi made her a star, but the public persona anointed by the film wasn’t a product of self-invention, rather, the projection of a nation. “Schneider’s image of the virgin was so deep-seated in Germanic memory that it became untouchable,” Marion Hallet writes in Romy Schneider: A Star Across Europe. A 1956 Der Spiegel interview with Schneider’s mother Magda was even plainer: “Why do people jump on Romy so much? Because they feel that there is finally a creature who has not come into contact with the filth of the world.” Schneider headlined more dramatically demanding films, like the 1958 remake of Mädchen in Uniform opposite Lilli Palmer, dextrously approaching the role with an austerity that breaks, at a crucial moment, into girlish delirium. The same year she returned to the ingénue period piece with Christine (1958), co-starring with an unknown French actor named Alain Delon.

La Piscine (1969)

That their romance would define an era was not yet apparent, even if it was clear that this seismic pairing of beauty was already major tabloid material. Schneider left West Germany and moved to France to be with Delon, turning up for an uncredited cameo in Purple Noon (1960), the film that made him, and those androgynous stiletto cheekbones, into the most beautiful man in the world. In March 1961, Visconti directed the couple in his stage adaptation of ‘Tis a Pity She’s a Whore at the Théâtre de Paris; he remarked that both actors had the “V of Rembrandt,” the same crinkle between the eyebrows that the painter included in his self-portraits. He then cast Schneider in his segment of the omnibus feature Boccaccio ’70 (1962) as a deliciously insouciant modern aristocrat contending with her husband’s predilection for high-end call girls. Striding through their palazzo swaddled in Chanel tweed, Schneider balances crafty self-possession with the transparently vulnerable, effortlessly landing punches like, “Daddy was happy we got married because of the prestige, but he never liked you much.”

Comedy defined, but was not the general rule, of Schneider’s Hollywood period in the early and mid-’60s. She appeared as Leni alongside Anthony Perkins’s Josef K. in Welles’s adaptation of Kafka’s The Trial (1962) and opposite Jack Lemmon in Good Neighbor Sam (1964) and Peter O’Toole in What’s New Pussycat? (1965), Woody Allen’s first produced screenplay. The industry didn’t—and still doesn’t—quite know what to do with a European actress, and Schneider wasn’t satisfied.

Over a decade before Rainer Werner Fassbinder courted, and lost, Schneider for the starring role of his 1979 film The Marriage of Maria Braun (negotiations disintegrated after Fassbinder called her a “stupid cow”; the writer Thomas Elsaesser cited Schneider as demanding, indecisive, and dependent on alcohol), Hans-Jürgen Syberberg filmed the actor for a role she approached with her typical resolve. Romy: Anatomy of a Face (1967), made for German television, caught the 27-year-old Schneider at a ski resort in the Alpine town Kitzbühel as she sought to negate the image linked to her celebrity. Speaking frankly on her desire for a different, more urgent style of work, the self-admitted “diva” with contempt for the “star system” once again disavowed her rarified archetype. She would continue that line years later, telling Paris Match in 1981, “I hate this image of myself. What am I still to people, if not still and always this little soap opera princess?”

Schneider’s very public breakup with Delon in 1963 upended her personal life (he left a note with a bouquet of roses in Schneider’s apartment, marrying a pregnant Nathalie Barthélémy not long after). The year she was documented for Anatomy of a Face, Schneider would star in two films with screenplays written by Marguerite Duras and begin a long-term collaboration with Michel Piccioli. She may have felt she was at a precipice. But after the drop would be the apex of her career.

L’Enfer (1964)

“She can be amazing when she wants to be,” her ex-lover Harry (Maurice Ronet) says to new lover Jean-Paul (Delon). The subject is Marianne (Schneider). The film is La Piscine. Schneider’s sylph in a maillot and patterned chiffon is also a journalist, spending her summer sleeping in and baking by their rectangular-cut rippling aquamarine jewel. Jacques Deray’s glacial thriller casts dark sexual intrigue over a sunny villa outside Saint-Tropez, and Schneider’s tanned body becomes the film’s visual obsession. But it is her restrained, penetrating performance as the ultimate witness that gives the film a kind of blunt force trauma. With costuming by Courrèges and an almost mute Jane Birkin, La Piscine’s covert nastiness and pseudo-bohemian libertinism accentuated the broiling chemistry of its leads and remains a lodestar for the glamorous and depressed. Delon pushed for Schneider to be cast. The press decamped to the Côte d’Azur to witness the reunion, angling for a rekindling of the “mythic” couple. (Delon and Barthélémy separated months before filming began.) “He says stupid things as I lay dripping over him in a bikini,” Schneider said. Delon would pursue Schneider for the rest of her life.

Even if Schneider usually seduced under bourgeois cover, she was not afraid of full exposure. Bernard Tavernier, who directed her in Death Watch (1980), one of her last roles, compared her to an opera actress. While Schneider passed on the lead in Liliana Cavani’s The Night Porter (1974), a concentration camp survivor in a sadomasochistic relationship with a former SS officer that went to Charlotte Rampling, her collaboration with Żuławski on That Most Important Thing: Love embodied the specter of the tragedienne. The gulf between the actor and the character could not have been further, or perhaps closer, depending where the whims of the public settled.

Nadine, once successful, is reduced to picking up roles in sexploitation films to support her husband (Jacques Dutronc). Her affair with a set photographer (Fabio Testi), who arranges for her to star in a production of Richard III, possesses her, even if she can’t supplant her despair. These images don’t appear in the final film, but snapshots from Żuławski’s set show Schneider drawing slashes of clown makeup on her cheekbones and nose with a tube of red lipstick. It feels antithetical to Schneider’s vulnerable transparency in the role, but the contradiction fits a woman who once said, “I’m bored of looking at myself in the mirror.” The abandon with which Schneider approached performances in this period—and her perfectionism—became her trademark. Paris Match said of Schneider in 1981, “Cinema’s good little girl…does not know where cinema ends and where her life begins.” Schneider was conscious of every frame she entered. In That Most Important Thing, she handles Nadine’s desperation like delicate glass. And she knows when exactly to smash it to the ground.

That Most Important Thing: Love (1975)

Share: