Columns

Cracked Actor: Magdalena Montezuma

On the transformative ascent of the chameleon actress.

Macumba streams on demand on Metrograph At Home.

Share:

In a 1975 interview collected in Foucault at the Movies, Michel Foucault gushed that Werner Schroeter was a liberator of bodies on screen. He kneaded bodies “like dough” until they became “anarchic, and hierarchies, localizations, and designations, organicity… all come undone.” For this revelatory pleasure, Foucault credited the director’s gaze, but what about the significance of his subjects? Most of the time this was Magdalena Montezuma: a bizarre, shapeshifting arthouse actress, who appeared in a smattering of West German films from the late ’60s until her death in 1984. Her extraordinary performances were their own anarchic undoing, smearing the borders between fragility and dominance, artifice and truth, glamor and the grotesque.

Her realm was the decadent experiments of her filmmaker friends—Schroeter, Ulrike Ottinger, Werner Rainer Fassbinder, Rosa von Praunheim, and Frank Ripploh, among others—where she darkened the dramatic outlines of terrifying divas, ancient tragics, and impish ghouls. Her face was the locus of all this intensity: she was part Silent movie star, part medieval Madonna, and like the changelings of centuries past, her appearance stokes both alarm and awe.

To get a handle on Montezuma’s great gift for metamorphosis, it’s best to start with Schroeter’s first full-length feature, Eika Katappa (1969). The film is an abstracted jukebox opera, where Montezuma cycles through various guises at breakneck speed: a nun experiencing stigmata; Tosca; a fandango-ing male suitor; a pitiful Rigoletto, waddling around with a hunchback; the legendary Germanic princess Kriemhild, weighed down by destiny and a set of giant blonde plaits. It’s dizzying. And yet, Montezuma embodies them all with ironic panache and a gestural grace. Your eyes never tire of her. She treats the set like a stage, elongating her movement for those in the cheap seats, and squishing her face into all sorts of surreal, shadowy shapes. It’s the kind of performance she would frequently be called upon to carry out in the trenches of underground cinema: to act as an envoy, guiding audiences through lands of gay, gilded pageantry and excessive ardor.

Eika Katappa (1969)

She was born Erika Kluge in 1943, in the Bavarian city of Würzburg, but she endured a childhood Victorian in its confinement and gloom. Much of her upbringing was spent indoors, sick with tuberculosis of the spine, watching the outside world through a mirror in her bedroom. She met Schroeter in the 1960s, when she was working as a bar waitress and studying literature, languages, and art history at a university in Heidelberg. She was depressed, and had just half-heartedly tried to kill herself by jumping off a two-meter wall. “Her attempt to end her life was rather comic and seems to me today more a suicidal urge in the pastoral tradition than anything,” the director quips in his memoir Days of Twilight, Nights of Frenzy. He first saw her in student productions of The Mysteries and The Maids, and was taken by her melancholic disposition and bulbous eyes.

They quickly became best friends, and ran amok across Europe, hitchhiking, idling in cafes, and making films. She also cultivated a practice as a visual artist (and would later go on to make costumes for theater). For Schroeter, women were freedom and passion personified, the cord that allowed him to string together gaudier beads from culture—homoerotic Genet-ian criminality, German Romanticism, Les Chants de Maldoror, lots of Maria Callas—to produce bombastic, fragmentary psychodramas. He had a cadre of actresses that were his regulars, but Montezuma was always his number one. Devotion on both sides never wavered, even if their relationship was a little tortured. She could be jealous of his lovers, and he, in turn, relied on Montezuma to serve as helpmeet. For a time, she tended to his correspondences with film labs and distributors and worked day jobs to support him, only to pile herself full of stimulants to work on his films late into the night.

It was Schroeter, and, according to Ingrid Caven, also Rosa von Praunheim, who renamed her, after the villainous starlet in Patrick Dennis’s parodic celebrity biography Little Me. But her acting had more in common with the mythical Montezuma, that Tohono O’odham tale, where the hero-god emerges from a hole filled with clay. She was a transformative force, who was shaped and remolded again and again.

Later in her career, she would even star as that most canonical chameleon of all, the titular Freak Orlando (1980) in Ottinger’s lurid riff on Woolf. Cue another overwhelming list: in the space of two hours, Montezuma goes from teat-suckling weary traveller to magical cobbler, to two-headed chanteuse, to chained vamp, to reptilian shy-guy driven to murder, to smarmy leather-clad hostess, rising to the occasion with vaudevillian showmanship and slapstick charm As preparation, Ottinger took hundreds of photographic studies of Montezuma, and in a way, the film operates as a cabinet of curiosities, with Montezuma as the main attraction, striking poses of dignified freakery and puppy-eyed longing.

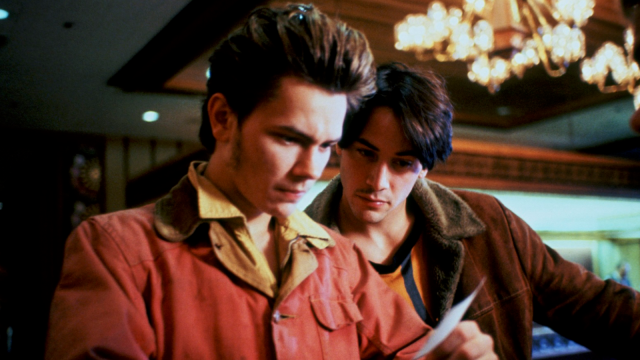

Taxi Zum Klo (1980)

Yet she wasn’t just some celestial being captured and put on display—she could also play the capturer or conspirator, relishing in proximity to power and ready to crack the whip. Just a year before Freak Orlando, Ottinger cast her in Ticket of No Return (1979) as “Social Question,” part of a Greek chorus of sociologists, wearing matching checkered suits, tsk-tsking the film’s heroine—a foreign socialite and extraordinary boozer (Tabea Blumenschein) who has come to Berlin to gulp down cognac until she drops dead. And in what would be the final installment of Ottinger’s Berlin trilogy, Dorian Gray in The Mirror of the Yellow Press (1984), Montezuma is a devilish but deferential secretary called “Golem” (another mythological creature born from clay), tending to the schemes of her mistress, the media scion Dr. Mabuse (Delphine Seyrig). Even when playing a nurse in Taxi zum Klo (1980), Ripploh’s touching, semi-autobiographical tale of a public schoolteacher seeking plenty of public sex, she’s sly, a bit sadistic, peering down at the protagonist’s asshole, as the doctor probes his anal warts with a metal rod. “See? Nothing to it,” she smirks, as he squirms on the exam table.

Montezuma’s expressive intensity teeters on the edge of the abyss. It will surprise no one that she thrived in roles of lunacy. The madness she depicted was not that of loose-limbed abandon, but more often an unnerving stillness. She would draw out the moment before an explosion, with hands that claw the air and eyes that dilate to cartoonish extremes. Gary Indiana called her “the greatest European actress since Anna Magnani,” and she shared the Italian actress’s capacity for bug-eyed rage and tremulous breakdowns. Both Schroeter and von Praunheim cast Montezuma as Lady Macbeth for their TV operas, which played back-to-back on German television in 1970. In that same year, she played King Herod like a simpering stoner, hornily stupefied by his stepdaughter, and ready to give everything up for one measly dance in Schroeter’s version of Salome (1970). And she’s a stand-out psycho in his Day of the Idiots (1981), as a patient who sucks the fingers of her fellow psych-ward maidens, and shrieks that for stabbing her husband, she really should be put in prison instead.

This is to say nothing of all those women she played whose infatuation and obsessions had set them down a path of derangement. Take Willow Springs (1973), which she wrote with Schroeter, while furious at him for marrying his childhood sweetheart for money. Magdalena plays “Magdalena,” a vengeful matriarch presiding over two desperate women (Christine Kaufmann as Christine and Fassbinder favorite Ila von Hasperg as Ila) at a derelict saloon in the Mojave Desert. All men who interrupt their idyll are killed, in retribution for a rape Magdalena survived at the house. No foot-stomping fit, no piercing scream, could ever get close to the crazed bereavement that Montezuma displays as she watches Ila have sex with a hitchhiker. It’s a scene of slow-mo disturbance and transfiguration. Montezuma presses her hands into the doorway and tilts her head back glacially, as a tear slowly slides down her cheek. In a few, brief movements, she morphs from the stock image of a femme fatale to that of a suffering saint—a trajectory also common in the oeuvre of Magnani.

In all of these transformations and unhinged episodes, Montezuma gets to the primordial core of diva histrionics; that urge that scratches at our consciousness from time to time: what if we were to let our emotions fully take over? No everyday tedium, no trips to the supermarket, no recovery—just writhing around on the floor in rhapsody or heartbreak! And what if this forfeiting of decorum didn’t necessarily mean you have to be an open book; you could still remain untouchable, elusive.

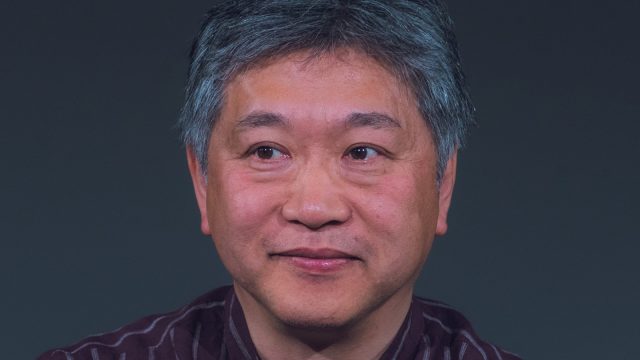

Magdalena Montezuma and Werner Schroeter

In so many of her movies Montezuma is a voyeur, staring down the object of her affection or ire. But there is one film made at the end of her life that complicates her reputation for menace and forbidding silence—Elfi Mikesch’s Macumba (1982). Here, Montezuma is a flustered, frustrated writer, living in squalor, trying to write a caper about a detective investigating a crime that has not yet been committed. Despite Macuba’s general mood of seedy dread, Montezuma plays her part with an uncharacteristic buoyancy—there’s a sense that her character is floating away with the story she has invented. While the film is centred on the loquacious reverie of the author, which stumbles and picks up pace in unusual places, it is mostly about how art is never immune from the dirty fingerprints of those who surround its creation.

This was inherent to the milieu of German cinema in which Montezuma moved. There were no delineations between art and life, and friends and lovers were the ones who plastered over the gaps left by lack of institutional support and money. In Fassbinder’s own meta-saga about this very cesspit, Beware of a Holy Whore (1971), Montezuma and Schroeter appear together. In one scene, the pair are sloppily making out, before Schroeter retreats, his hand still holding Montezuma’s face. “You should clean your teeth,” he says. She pushes him off, sulking, “Stop mauling me!” Montezuma’s character, the jilted lover of the film’s maniacal director, was a stand-in for Irm Hermann, Fassbinder’s former leading lady and ex-girlfriend, whom he didn’t want to deal with on set—but whose voice would be dubbed over Montezuma’s in the final cut.

Montezuma’s own voice is missing from the record. What little information we have on her (at least, in English) comes second hand, from friends who were also her closest artistic collaborators. Perhaps this is just the quiet nature of minor avant-garde stardom in postwar Germany. Or maybe she never submitted to interviews due to her alleged terrible shyness: “Sometimes, when we were in a bar or restaurant, I had to accompany her to the toilet because she didn’t dare cross the room,” remembered Caven in 2024. What emerges from these recollections is a woman starkly drawn: needy, domineering, prone to dark mood, unlucky in love, incredibly talented but self-critical, who succeeded in destroying the majority of her paintings and drawings (her friends managed to salvage only a few pieces from the rubble). Her identity is hard to grip and slips into the puddle of persona, dissolving into the melancholy madwomen and imposing prima donnas she incarnated. Rising to the surface are the glimmering shards of worship she inspired—Indiana: “I adored her,” Schroeter: “She was the leading lady, the expression of my soul.” In Swiss filmmaker Daniel Schmid’s Do everything in the dark in order to save your lord the light (1970), one the film’s 14 acts is dedicated to her, titled “Mass for Magdalena Montezuma.”

In 1982, just before her 40th birthday, Montezuma was diagnosed with terminal cancer, and Schroeter quickly got to work on her swan song The Rose King (1986). The filming wrapped just a month before her death, where she had joked constantly about her desire to die on set. Montezuma plays a delirious owner of a rose farm in Portugal, caught in an unholy trinity between her insolent son, and the love interest he’s imprisoned in a barn filled with goats. Here, the deathliness that crackles throughout all of her performances comes into stark relief. She is a sick woman, with bone too close to skin. Schroeter directs with a kind of desperation, shuttling through images of cobwebbed interiors, wet roses, fireworks, soapy bodies, and Montezuma over and over, gazing out of grimy windows and smearing black paint all over her gaunt face. It is a spectral rendition, but one where her ability to collapse boundaries still reigns. Decay and beauty, perfection and wildness, ecstasy and erotics, are not just intertwined, as is usual in Schroeter’s films, but mashed together in a thick, florid paste and made indistinguishable. Montezuma’s final transformation on- screen is one of earthly release—we watch as she lets go of roses, relationships, and her failing body.

At the end of his life, dying from the same cancer that had killed Montezuma, Schroeter would lament she was an irreplaceable figure in his films: “I have never found one to succeed her fully,” he said. Her absence would come to haunt his corpus. In Deux (2002), Isabelle Huppert tells Schroeter’s biography through the prism of identical twins separated at birth. One is named Maria, after his beloved diva queen Maria Callas. The other is called Magdalena.

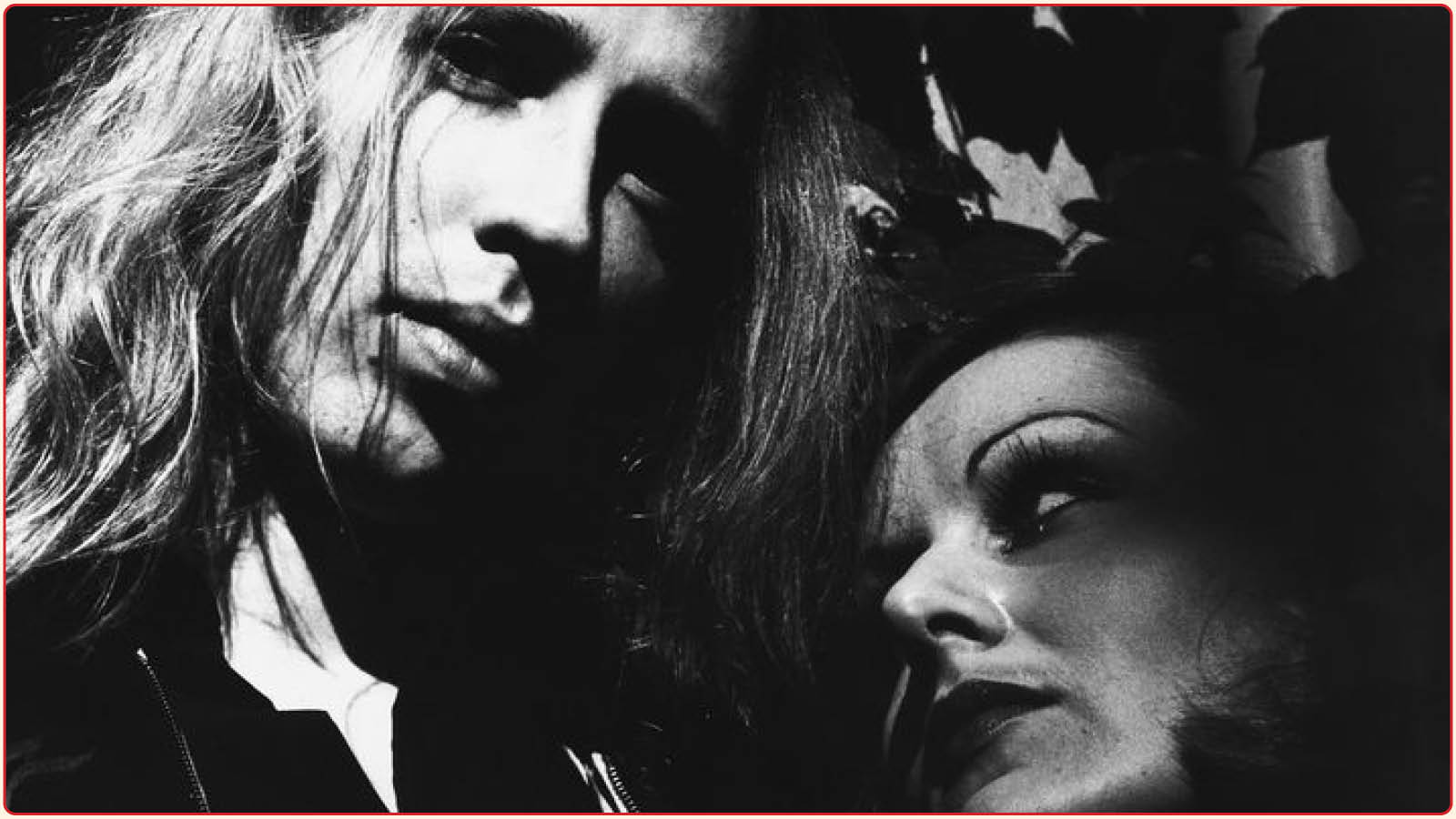

Willow Springs (1973)

Share: