Essay

Pink Narcissus

On the broken bedroom visions of the ’70s gay cult classic.

Pink Narcissus screens at Metrograph from Friday, April 11.

Share:

A bedroom can be a garden. Fantasies sprout from a mattress. Urinals flush. A butterfly performs fellatio. Seed spills across body and coverlet. New growth arises, fertilized by the rot of the old. Eventually reality intrudes. A telephone rings. Money must be made, sheets tossed aside, waistbands snapped, appointments kept, deadlines hit. You get the picture. James Bidgood didn’t, not entirely. As he said in an interview in 2006, “Every day of your life is just another dream.”

Pink Narcissus (1971), Bidgood’s lone realized film, fantasizes about endless erotic fantasizing. With a simple premise—a comely male prostitute (Bobby Kendall) lolls around his apartment and loses himself in amorous visions between visitors—it poses questions like: what if you could jerk off forever? What if you never had to finish a session, or a movie, but could instead live inside one clear to Judgment Day? What if that was heaven, self-contained and self-containing? What if the world never barged in, only blew gently through the window as fragmented sense data for assembly into masturbation material?

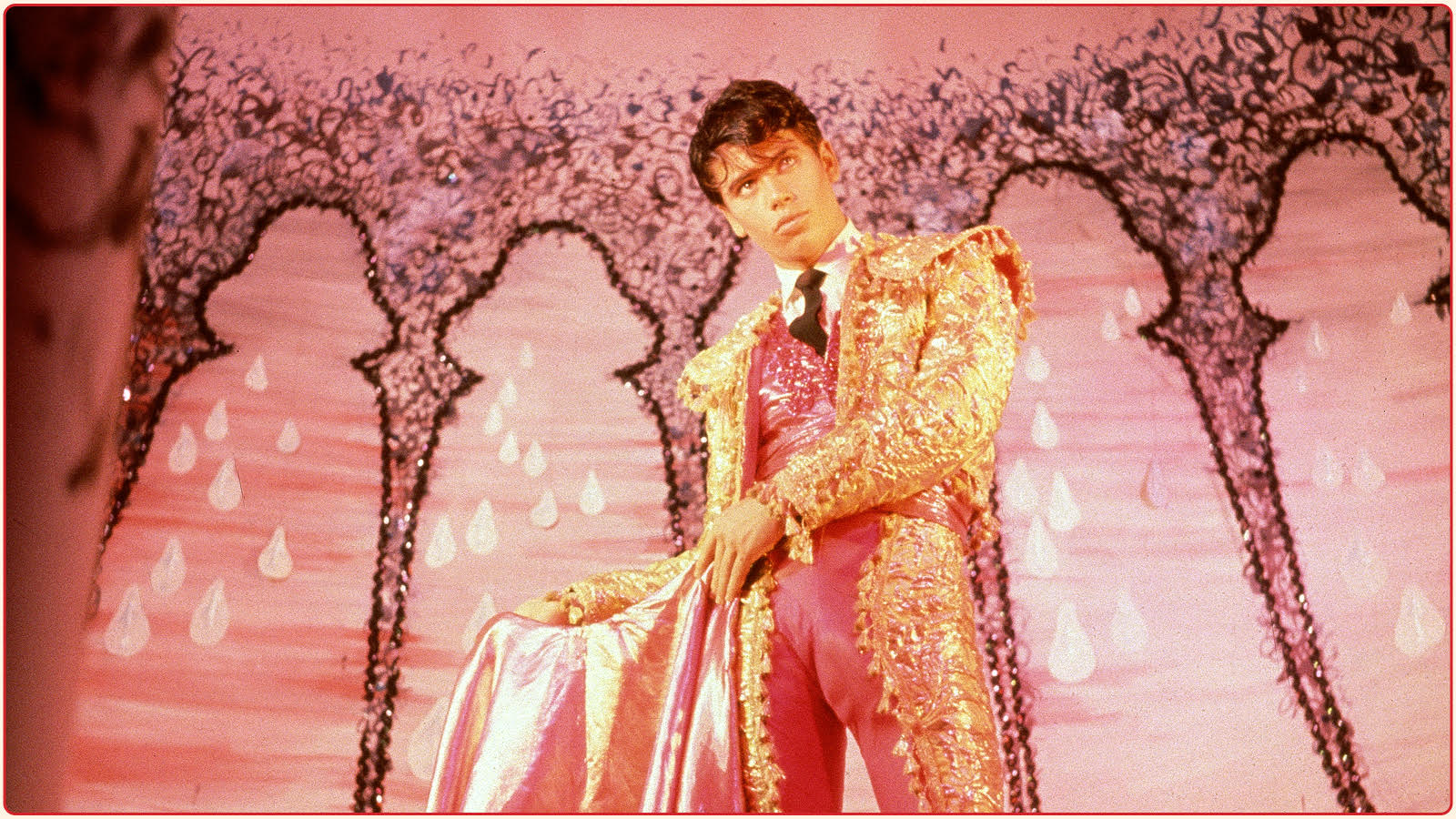

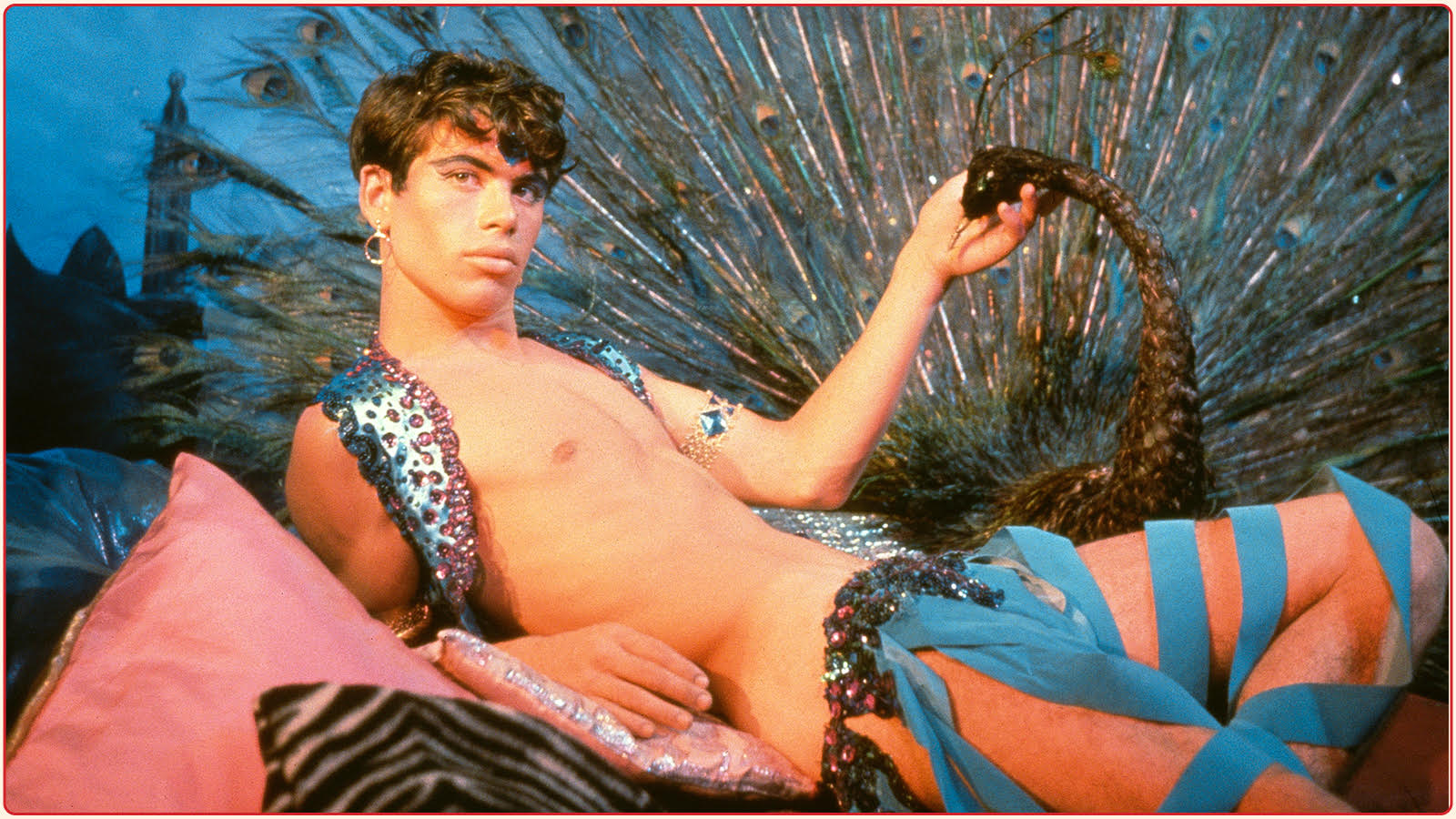

You wouldn’t need a plot, for one, and Pink Narcissus doesn’t have any. Instead it has yellow. It has blue and violet and blinding white and, yes, pink. It has outrageously electric Kenneth Anger color playing across the face and flexing body of its star, the Adonic, reportedly straight, reportedly inept hustler Kendall. And it has lush, romantic, minutely detailed sets, all engineered through painstaking effort between 1963 and 1970 by Bidgood, almost entirely in an alcove of his small Hell’s Kitchen apartment, with scenes shot piecemeal, mostly on 8mm and then later 16mm film. It also has a bed where Kendall lounges, his erection draped over one leg, and escapes into a circus of self-consciously artificial scenarios of sexual ecstasy and domination. The whole affair lasts little more than an hour. Bidgood, who died in 2022 at age 88, hated it.

Pink Narcissus (1971)

“I can’t even hardly look at it,” he said in that same 2006 interview. Bidgood, a devotee of Ziegfeld Follies, moved to New York in 1951, where he became a drag queen, a ballgown designer, and a photographer who stripped his disused gowns for parts and draped them over the ephebic men he shot against sumptuous backdrops of his own construction for physique magazines and one-offs. A major influence on artists like Pierre et Gilles and David LaChapelle, he was an original and a perfectionist more invested in pleasing himself than the impatient johns of the movie business who had put up some of the money for Pink Narcissus.

Tired of waiting, Bidgood’s financial backers infamously took the unfinished film from him in 1970, handed it to an editor, Martin Jay Sadoff, who also worked on the score, and then released it the following year. In protest, Bidgood pulled his name from the project, which credits “Anonymous” as director, producer, writer, and photographer. The film emerged shrouded in mystery, its creator rumored to be Anger or Andy Warhol. It premiered the same year as Wakefield Poole’s Fire Island–set hardcore romp Boys in the Sand, to audiences far less shocked by gay softcore fare than they would’ve been in the ’60s, when stringent censorship laws still remained in place. Bidgood continued taking photographs and, later, styling beds, background acting, and laboring over a never-finished musical titled FAG. But the loss anguished him, and his second and final attempted feature, the hardcore effort Beyond These Doors, dissolved after Bidgood blew the whole budget on a single orgy sequence, “Baghdad,” which appears in 1975’s anthology film Good Hot Stuff.

As the writer Elizabeth Purchell has noted, Bidgood was fingered by publications like Variety and The Advocate as Pink Narcissus’s author in the ’70s, but the facts weren’t widely known until the writer Bruce Benderson tracked him down decades later, “outed” him (per Bidgood), wrote a monograph on Bidgood for Taschen, and ultimately ushered the film toward gay cult classic status, which must’ve rankled Bidgood at least as much as it pleased him. Fans five-star his broken dream on Letterboxd. A distributor has completed a new restoration that cinemas will screen for younger generations. What we have, what we love, what is beautiful, exists because the original distributor, Sherpix, who helped fund the movie, intervened. What does this mean? That Sherpix was right to wrest the film away from its creator? That right and wrong don’t factor as such, only the pain felt by Bidgood from losing control over his magnum opus and any opportunities that might have resulted from his association with it? We can’t know whether Bidgood’s cut would’ve been “better,” or whether it would’ve come out at all. But we know he suffered.

Pink Narcissus (1971)

To work at and for himself, to be his own john: this is another way of describing Bidgood’s lodestar fantasy, and that of his protagonist, too. Kendall plays a call boy more excited by his daydreams than the prospect of turning tricks. He lurches from one scenario to another. (Here you might credit or discredit Sadoff: the transitions tend to be jarring sonically and visually.) Often Kendall plays more than one role: slain and slayer, master and slave, hustler and john. Other figures swirl around them. His imaginarium is peopled, like all imaginariums, with disguised shards of himself, including these multiple, contrary roles. After all, he is a Narcissus, enthralled by his own visage, and his desire feeds on itself, like an ouroboros or a guy in a self-suck vid.

Dressed briefly as a toreador, Kendall tempts a leather-clad biker with a square of gauzy fabric. We can see through the material; we know that on its other side there is nothing but air. But the biker charges forward, lured by this sheer layer of cloth Kendall drapes over empty space. Elsewhere Kendall portrays both a Roman emperor and his tortured sex slave, a sultan and his catamite. For this sultan a third man dances, his erection flapping near his navel, its visibility and allure heightened by the millimeter-thick underwear that fails to conceal it. For Bidgood, the contrived imposition of a flimsy piece of material that mediates between eye and flesh supercharges desire: we know what to expect, we like what we see, we like just as much expecting to see it more, and we quite like the game of it all, too.

That rude thing, reality, buzzes incoherently in the background of apartment scenes as a voice from the radio. It announces labor unrest and stock market movements. Kendall doesn’t care: he’s horny. Unbothered, he spins a bejeweled telephone’s bejeweled dial. He plays a bejeweled record and a voice sings: “I’m so lonely.” Outside, in a grungy haunted-house version of Times Square, desire runs amok. The stage actor Charles Ludlum sells “pissicles.” Priests disrobe. Construction workers and fetishists massage long soft cocks. Bag ladies trundle by and vampiric johns in bowler hats place calls in a phone booth. “Get ‘em while you’re hot,” reads one sign. Desire and terror dance together in the street, becoming coterminous. Lust unleashed, uncontained, threatens to unmake the world.

Kendall keeps inside, safely alone, until a john finally walks through his door. A moment later, the man transforms into Kendall himself. Pink Narcissus is a paean to self-regarding beauty, filmic and masculine both, and to their right to self-regard. (Narcissus has, of course, always been his own object.) Our pleasure lies in watching, not participating. After all, this is a film, one that’s ending. But then, as Kendall-john gazes into the screen, it cracks. The flow of images halts. Has he seen us? Have we killed the mood, intruded? Seconds pass and the crack becomes a cobweb, the cobweb an accoutrement of an Edenic setting where Kendall earlier stuck his dick in the ground and fucked the ersatz Earth. We’re back in the garden. Are we ready for more?

Pink Narcissus (1971)

Share: