Column

Cracked Actor: Michelle Pfeiffer

Batman Returns (1992)

Column

BY

LUKE GOODSELL

On the empathetic performances of the superstar actress.

Piping Hot Pfeiffer opens at Metrograph on Saturday, June 22.

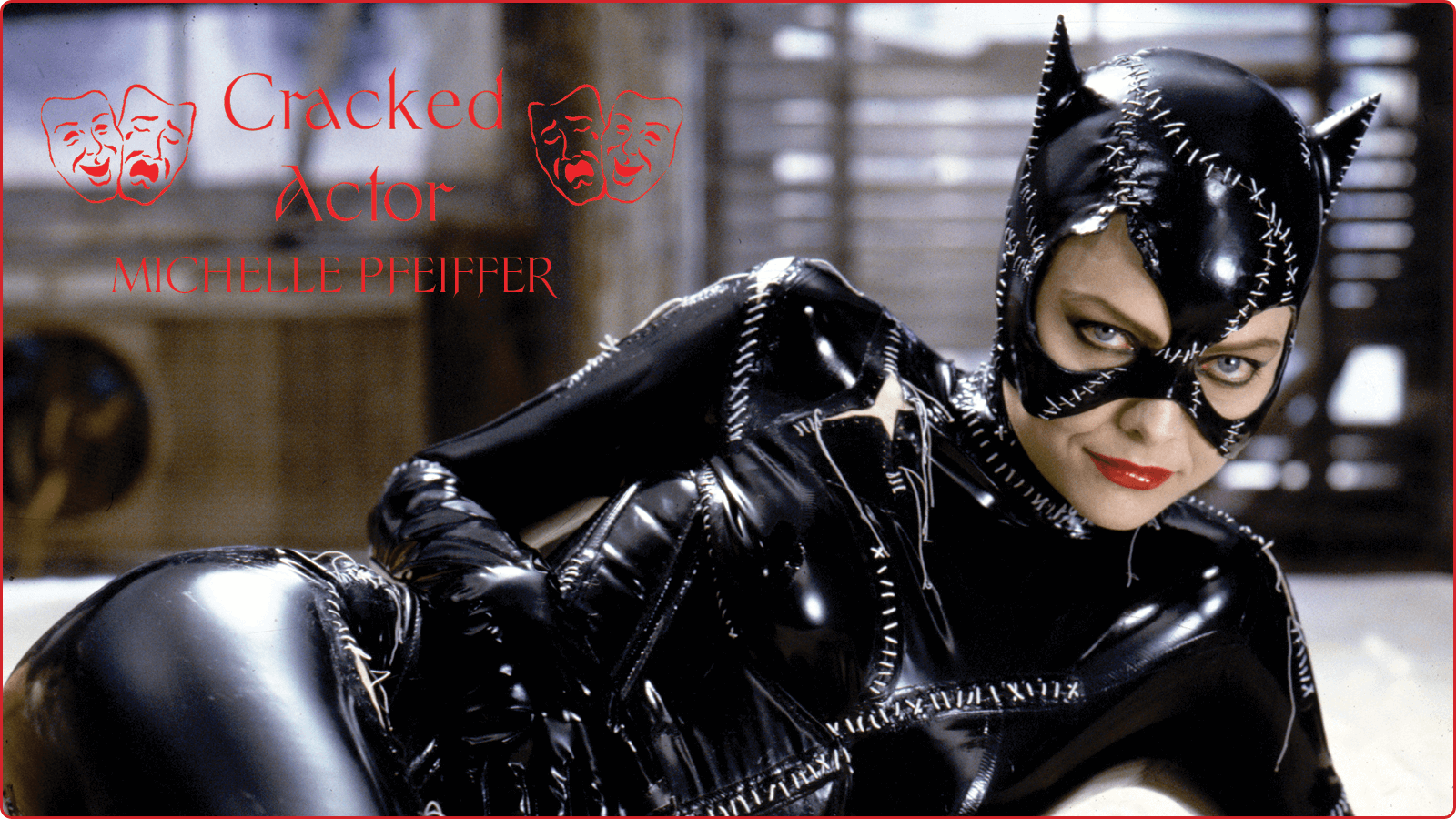

“Life’s a bitch,” snarls Michelle Pfeiffer’s Catwoman, avenging anti-hero for the Riot Grrrl era, midway through 1992’s Batman Returns. “Now, so am I.” It may not be her most subtle work, yet there’s something about that brash, bratty aphorism that cuts to the essence of the former SoCal pageant queen turned Hollywood’s most luminous-and perhaps unusual-late 20th-century superstar. The line on Pfeiffer has long been that she had to prove her talent against the limitations, such as they were, of her remarkable looks, but her beauty-and the ways in which she toyed with and subverted it-is inseparable from her craft onscreen. No two Pfeiffer performances are the same, yet each is infused with her gestural flair, her essential humanity, and her empathy for eccentrics and outsiders.

For all of Pfeiffer’s pop culture ubiquity throughout the ’80s and ’90s, few multiplex stars were as elusive, as hard to get a handle on. Though a sex symbol, she was never a femme fatale like Sharon Stone; she could play quirky and romantic, but she wasn’t an American sweetheart like Julia Roberts or Meg Ryan; a serious talent, she was rarely considered in the company of Meryl Streep or Jodie Foster. None of them, of course, could go toe-to-toe in a warehouse with Coolio-as Pfeiffer did, cheekbones tilted to infinity, in the rapper’s iconic music video for “Gangsta’s Paradise”-let alone whip heads off mannequins while shrink-wrapped in a leather cat-suitor hold a live bird captive in their mouth. (Surely the wildest performance in a multi-million-dollar blockbuster with a Happy Meal tie-in.)

Married to the Mob (1988)

Pfeiffer’s unlikely journey from surfer chick to super freak might begin with her childhood relationship to her image. “When I was very young I never thought I was attractive,” the self-described tomboy, nicknamed “Michelle Mudturtle” in elementary school, told Interview in 1988. “I looked like a duck.” Born to working-class parents in Midway City, Orange County, the young, wild-child Pfeiffer spent a listless adolescence hanging out with surfers at Huntington Beach and working a checkout job at Vons, before entering, and winning, the Miss Orange County Beauty Pageant in 1978 (“A softball player who also oil paints, she’d like to become an actress,” announced the emcee). A run of movie and TV bit parts followed, invariably featuring the aspiring starlet in hot pants or padded bras (she was billed only as “The Bombshell” on the 1979 series Delta House). Her first major role arrived in 1982’s ill-fated Grease 2, as the gum-snapping gang leader of the Pink Ladies: sassy in leather and full of bad-girl longing, like Debbie Harry if she’d been a Shangri-La. When the movie flopped, she could barely convince Brian De Palma to cast her in his 1983 remake of Scarface. It turned out to be a career-maker. Gliding into the picture in a bias-cut silk dress as zonked-out trophy wife Elvira Hancock, she’s colder than Giorgio Moroder’s beats, all elbows and doomed malaise: a disdainful, dead-eyed foil to Al Pacino’s hubristic Cuban drug lord. Debuting the killer eye-roll that would become an ace in her arsenal, Pfeiffer’s Elvira is a mistress of the dark whose soul is more corroded than the criminals she’s caught between-a rotted avatar of WASP consumption and American complicity.

Pfeiffer’s performances in both films-sizzling with “don’t call me baby” insouciance-have a sly, comedic edge; she knows when to play off and when to undercut the tough-guy pretense with which she’s surrounded. Still, it would take time before Hollywood recognized the gift beyond the glamor. If George Miller’s The Witches of Eastwick (1987)-a pop-feminist whirligig in which Pfeiffer, Cher, and Susan Sarandon summon the devil (Jack Nicholson) to do their bidding-had tapped the actor’s comic abilities and made her a marquee star, then it was Jonathan Demme’s Married to the Mob (1988) that opened up her full, expressive range as a performer. Outfitted in leopard print, frosted lipstick, and a Long Island accent, Pfeiffer’s low-rent mob princess on the lam sparkles with charisma and screwball timing-not to mention a ferocious right hook, delivered to camera, and by extension, any lingering doubters. The performance showcases Pfeiffer’s keen sense of rhythm, her versatility, and empathy; fusing inventive physical comedy with emotional vulnerability-her posture can sharpen and slacken on a dime-she transforms what might have been a caricature into a rich portrait of a woman stumbling toward a liberating sense of self.

Her first Best Actress Oscar nomination would follow for 1989’s The Fabulous Baker Boys: as a call girl turned sultry lounge singer (immortalized in a red slip dress writhing atop Jeff Bridges’s piano), she conveys the frayed, hard-bitten complexity of an outcast scrambling for her piece of the action. She would earn her second nomination as a Sirkian housewife who falls for a drifter (Far From Heaven‘s Dennis Haysbert) in Love Field (1992), which showcased another brittle beauty desperate to escape her repressed conditions.

The Fabulous Baker Boys (1989)

-Where other stars cultivated their allure on- and offscreen, Pfeiffer-a chameleon in the shape of a Golden Age siren-sought out unconventional modes of glamor, gravitating toward women held together by gum, hairspray or, as befit the work, a corset. Her characters were often out of sync with their surroundings, crackling with a force at odds with their modest physicality. She’s never more electric than when freed from the politesse of society and the expectations placed on femininity. It’s there in the way she allows her tongue to roam across her cheek while sewing her catsuit, savoring every euphoric drop of abandon; in the ease with which her laugh could escalate from beguiling to psychotic in the space of a breath; or in the way her walk might break into an angular waddle-an amusing reminder of her character’s unease. (Cher affectionately described her as “the clumsiest woman I’ve ever met.”) Even her period roles embodied outsiders ostracized by-or at the mercy of-prevailing social mores. In Stephen Frears’s 1988 costume romp Dangerous Liaisons, for which she earned a Best Supporting Actress nod, Pfeiffer is the virtuous, unattainable politician’s wife who unravels after she becomes a mark in a game of cruel intentions; caught in another love triangle in Martin Scorsese’s The Age of Innocence (1993), she’s a scorned and scandal-ridden countess at odds with Edwardian New York, her emotions as tightly coiled as her crown of curls.

“Basically, she’s a character actress,” Al Pacino told Rolling Stone in 1992, after the Scarface duo reunited for 1991’s Frankie and Johnny, a drama about the relationship between a down-and-out waitress and an ex-con short-order cook. Playing a Miller-chugging spinster who lives in a crummy studio apartment, Pfeiffer is raw and unadorned, a tender study in dead-end dreams and deferred desire. It’s a measure of Pfeiffer’s peculiar talent that her most moving scene is also the film’s funniest: surveying the quotidian lives of her neighbors from her apartment window, she seems to take on all the loneliness of the world-until she starts choking on the oily peanut butter she’s been spooning straight from the jar, sounding for all the world like Donald Duck.

Pfeiffer’s white gold rush of stardom-the magazine covers, The Simpsons guests spots, and box office receipts-also augured an inevitable degree of conventionality, albeit in roles jazzed by her off-kilter sensibility: as a romantic lead opposite Robert Redford (Up Close and Personal, 1996), George Clooney (One Fine Day, 1996), and Bruce Willis (The Story of Us, 1999), or an ex-marine turned unorthodox, inspirational teacher of troubled Bay Area teens, in one of her biggest hits, 1995’s Dangerous Minds. (Between her tête-à-tête with Coolio, Bruno Mars’s shout-out on “Uptown Funk,” and the cult of Scarface, Pfeiffer’s relationship with the hip-hop world needs to be studied.) By the time of her last headline smash, at age 42, in Robert Zemeckis’s Hitchcock riff What Lies Beneath (2000), it felt like the multiplex was running short on ideas to match her talent.

The Age of Innocence (1993)

A knockout supporting turn as an incarcerated mom in White Oleander (2002) prefaced a self-imposed, five-year hiatus, after which Pfeiffer returned to find that, nearing 50, the playing field had changed. “I want to be allowed to age gracefully,” she’d said to Premiere in 1993, “but they don’t let you do that in this business.” There would be the usual offers of witchy hags and thankless superhero parts, a roster occasionally seasoned with a delicious diva, like her imperious, aging beauty queen in the 2007 remake of Hairspray, complete with a catty showstopper as catchy as it was cruel. The one film that worked to suggest a path less traveled-Amy Heckerling’s comedy I Could Never Be Your Woman (2007), starring Pfeiffer as a 40-something TV producer who takes up with a 29-year-old actor, played by Paul Rudd-got lost in studio disputes and went straight to video; nobody saw it. Heckerling’s movie gives Pfeiffer the chance to play against the older-woman straightjacket (she’s more of a teenager than her 13-year-old daughter), and unleash a withering dismissal of an ageist studio executive-“Listen you little man… you’re not worthy of kissing Cher’s tattooed ass!”-that seems to channel every actress who’s ever been prematurely put out to pasture. Either way, she appears to have negotiated a comfortable legacy path through professional middle-age, mixing prestige television with supporting roles as loopy matriarchs (2012’s Dark Shadows; 2017’s mother!) and the occasional character piece-like Azazel Jacobs’s French Exit (2020), with a typically oddball Pfeiffer luxuriating in every droll put-down as a gilded widower with a death wish and nothing left to lose.

My favorite image of Pfeiffer is a publicity still from Batman Returns, depicting her in character as Selina Kyle, bandages on her forehead and around her hands, hair a perfect mess of blonde curls; beaten but not broken, she seems to bear witness to every Pfeiffer heroine. In the movie, she’s just been pushed out a skyscraper window by her boss, brought back to life by a gang of street cats, and trashed her apartment and all its stereotypical signifiers of girlhood-Pfeiffer understands that Selina is the mask, that femininity and beauty are a performance to conceal the chaos within. One of Pfeiffer’s greatest moments remains the scene where she’s laid out in the snow after that fall, her eyes rippling and rolling back into her head as though powered by some spooky, possessed animatronic. It’s a high-wire feat of expressionist daring, a tribute to both Pfeiffer’s uncanny physicality and emotional imagination.” Her eyes look like a special effect,” the film’s director, Tim Burton, told the Hollywood Reporter in 2017, “but that was all done by her.”

Luke Goodsell is a writer, editor and festival programmer.

Batman Returns (1992)