Double Exposure: Davy Chou and Kavich Neang

Column

DAVY CHOU AND KAVICH NEANG

Column

The filmmaker friends and collaborators discuss the influence of Cambodian history on their work, and the thin line between documentary and fiction.

From Producer to Director: Davy Chou Presents opens at Metrograph on Saturday, June 22 both In Theater and At Home.

“Interviewing” a friend can be an unusual exercise. Kavich Neang and I have known each other for such a long time, it might seem that we know what to expect from each other’s answers. But it also presents an opportunity for shared reflection that we might not otherwise undertake, perhaps precisely because we feel we know each other so well.

I created the film company Anti-Archive with Kavich, along with Taiwanese American filmmaker Steve Chen, 10 years ago. I’ve produced Kavich’s last five films (three shorts, one feature-length documentary, and one feature), and I see him nearly every week in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Kavich was born in Phnom Penh in 1987, in the aftermath of the Khmer Rouge genocide, which already makes our perspectives and personal stories so different, since I was myself born in France, where my parents were fortunate enough to move, two years before the fall of Phnom Penh in 1975.

Kavich grew up in the White Building, an iconic Phnom Penh building from the ’60s and a symbol of the Khmer New Architecture (a style that was later on abandoned during the war, although the White Building was repopulated in the ’80s). Nearly all Kavich’s works have concerned this building somehow: whether occupied or passed through by his characters, or as the central subject of the film itself, as if he has had to fully embrace and confront this obsession to allow himself to move forward. What I find particularly fascinating and unique is that he made both a documentary—Last Night I Saw You Smiling (2019)—and fiction—White Building (2021)—on the same story, a gesture that reminds me of Dong and Still Life (both 2006) by Jia Zhangke, who, coincidentally or not, co-produced White Building. In fact, Jia has often expressed his love for The Bicycle Thief (1948) and the parallel with Italian neorealism feels relevant while discussing the post-genocide work of Kavich, who captures the reality of contemporary Cambodia and the daily life of its inhabitants.

Speaking with Kavich over Zoom, I could feel my theoretical, European-trained orientation challenged by his intuitive approach, which has been shaped by the two years he spent making documentaries under the mentorship of Cambodian filmmaker Rithy Panh, as we explored our respective practices, work, methods, and experiences. —Davy Chou

DAVY CHOU: Hi Kavich, nice to talk to you. We know each other well, but maybe we can start by asking: do you remember our first interaction?

KAVICH NEANG: We met in 2010 when you started doing cinema workshops at your home near Central Market [Phnom Penh]. I joined every Sunday because I had a class in the daytime. That was my first time exploring cinema seriously. You were explaining all the details—like the shot, the script, camera movements, lighting and colors, all that—that’s what made me intrigued to learn about cinema, without knowing that I was getting connected to it. After that, I told you that I was interested in studying cinema and you told me that there was no film school during that time; and then you introduced me to the Bophana Center, founded by Rithy Panh, and that’s how I began to study documentary.

How about you? What made you really want to do those cinema workshops?

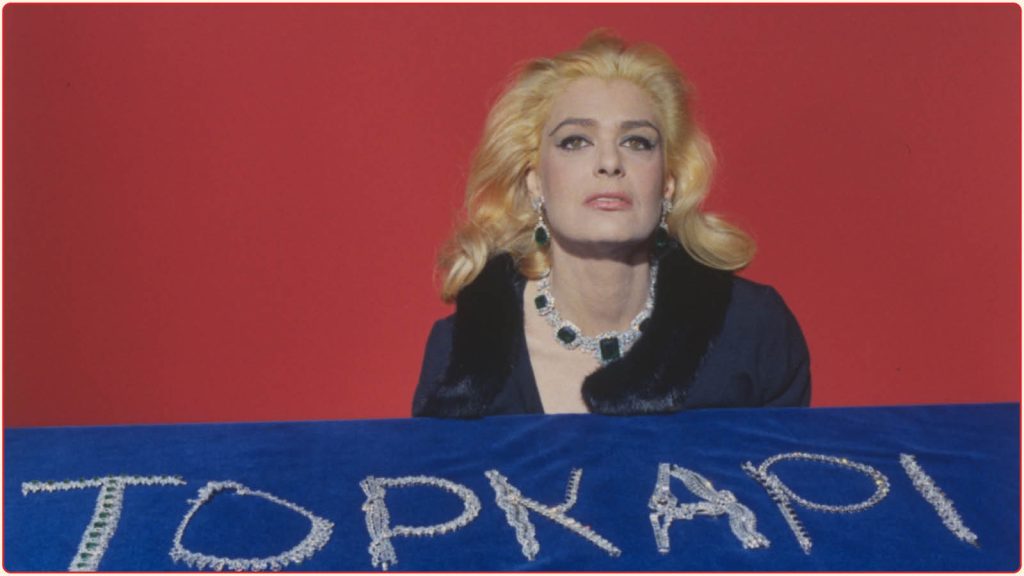

Return to Seoul (2022)

DC: I was mainly looking to have an activity during my first time [in Cambodia], just to be busy and have something to do, that could somehow be an alibi for what I really wanted to do:exploring the country, getting to know the people, living there. I ended up staying a year and a half. That was from early 2009 to mid-2010.

I remember you started asking very specific, sharp and relevant questions. I felt, like, “This is not someone who’s discovering cinema now, this is someone who’s already been in touch with it; who’s already been asking questions and has a very specific eye. That’s what I remember—with a little bit of a smart-ass vibe. [Laughs] We connected, and afterwards we worked more together and collaborated on Smot (2010), a short film that you directed and I produced for the German cultural center Metahouse. After that, we collaborated on many things.

I wanted to ask a question that relates to both of us, about the fact that you’re a director of both documentaries and fiction. You started out making documentaries and then began making features. Similarly, I made a feature-length documentary first [Golden Slumbers, 2011] and after that three fictions. How much do you think training in documentary impacted your work in fiction, and how do you navigate that? And do you think your fiction embodies more documentary aspects than other fiction directors?

KN: I was inspired by documentaries to make fiction films. I really don’t know how to start a story that I don’t know; it’s difficult for me to think of a fresh story. For example, when I made Last Night I Saw You Smiling, I felt comfortable really going through all the details. Maybe I reflect faster making documentaries? I feel close to the characters that I’m filming;I don’t need to think what they think, I just need to be close to them, to capture every moment.

With fiction, there needs to be a structure, a script, an actor. With documentary, it’s easier because you don’t know what might happen.

DC: Interestingly, for me, I think my relationship to documentary is very different. I was always thinking of fiction while starting to make films. My references, my models, the films that I grew up loving, were more fiction than documentaries. Making a documentary as my first film was a constraint. When I was in Cambodia, I quickly understood that a fiction film it would have cost a lot of money. I made the documentary because I could not do something else on that topic.

Having said that, when I switched to fiction, making Diamond Island (2016) and Return to Seoul (2022), there is a strong documentary aspect in both those films. Making that first documentary, even though it was not a choice, shaped my practice. Now, I feel it’s important to welcome the surprises of reality, and not only be in the bubble of pure fiction. But secondly, it comes back to the heritage of a thing that I love as well, which we can call naturalism.

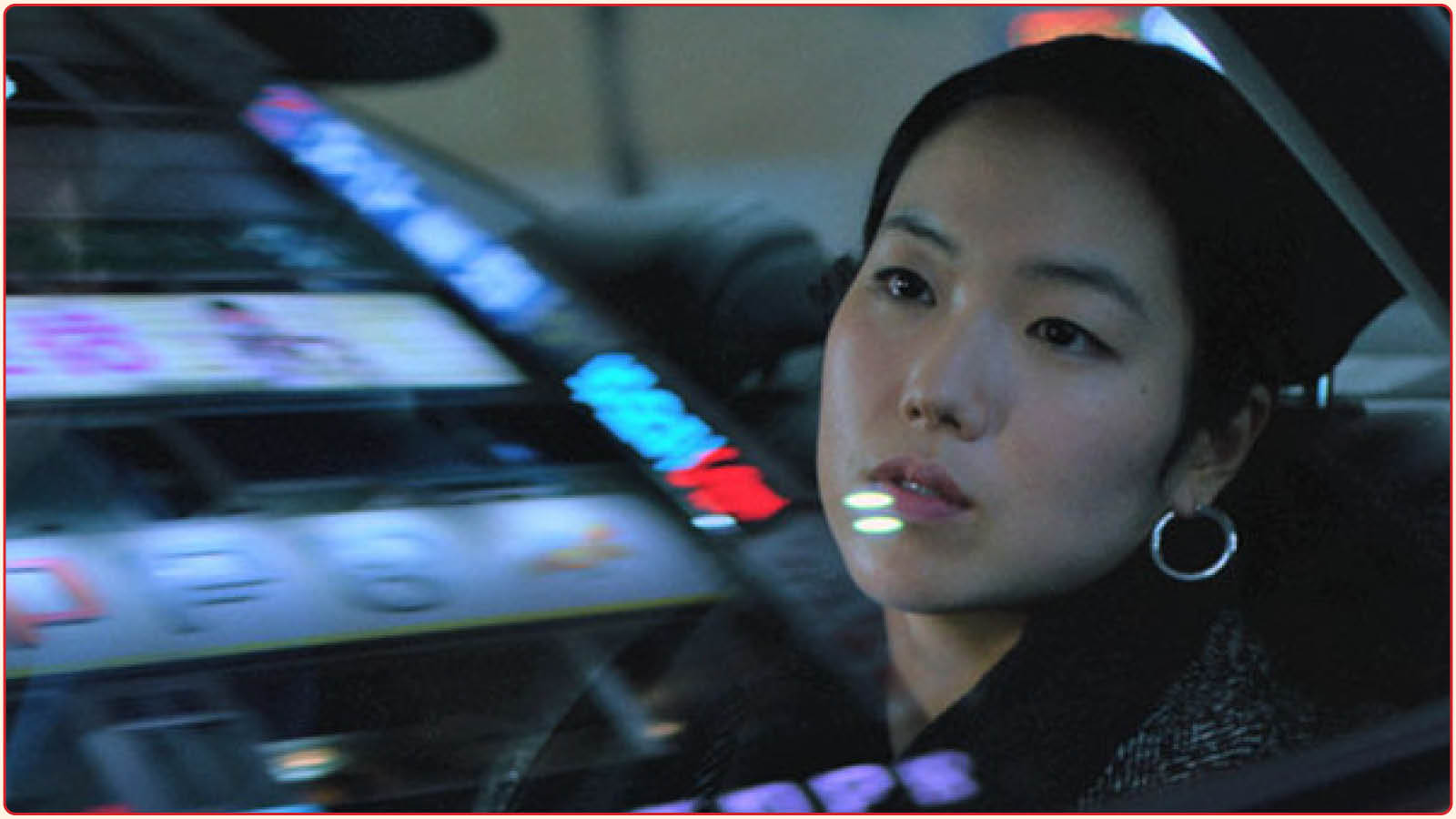

Last Night I Saw You Smiling (2019)

DC: Yeah, I was about to ask, since you know and read lots of stuff, how do you make [the film] your own? Like, talking about Return to Seoul, it’s about finding identity; so it’s really coming from the knowledge that you have.

DC: Yeah, it’s about that, and I think eventually it’s about dealing with freedom. As artists, we are looking for the answer to the question of how to be free as a filmmaker. How do you deal with that notion? Do you also struggle to find this place of freedom?

KN: Yes, of course. When I think of freedom, for me [as a director], it’s about trying to pretend that you don’t know anything: meaning that you try to follow the character, rather than just listen for what you want. Because each character has their own expressions and their own way of leading their lives. I think that [approach] can give you a unique way of telling the story.

For example, when I made Last Night I Saw You Smiling, people always asked, “Do you create a style before you’re shooting? Do you have a style already?” But basically, the style is coming not from me, because I don't have equipment; I have only one camera, a DSLR, a small one. And then the topic: it’s about people packing and moving, on the last day before they leave their home of many years. So I was like, “Okay, how can I capture that moment?” Because of the lack of resources, the lack of time, I felt I should trust what I could see in front of me. This creates its own style. Going back [to your original question], the freedom is not coming from me. Maybe that’s how I look at cinema now.

DC: It’s very interesting. Something I was a bit obsessed with when making Return to Seoul was the loss of control. To lose control, for me, was to reach that freedom. It was particularly key for me because there’s some kind of control freak aspect of my work. I prepare a lot—the shot list, the little details. I talk with my team, and bring a lot of people into the process reflecting on the form, to find the right way of shooting and breaking down each scene.

But Freddie, the main character in the film, is someone who defies categorization and any attempts to control her. Any time that people try to dictate to her who she is or what she should do, she reacts strongly, bringing chaos. I identified that that would be the core of the film, the force of the character. I think it was really meeting with the actress herself, Park Ji-min, because she, not the character but her as an actress, she resisted as much as Freddie, because that’s her personality. That’s maybe why I had this instinct to offer her the role.

We had a very good relationship, but sometimes we also had moments of tension. And although it was one of the biggest challenges for me, I’m grateful because it brought me what I was hoping for theoretically. And anyway, film is always about losing control, because it’s impossible to control exactly what you want: you are dealing with reality, with people, and a huge machine that is shooting. I really found myself in a moment where I had to let go and it was a learning experience for me.

Golden Slumbers (2011)

KN: But do you see yourself somehow as a character, too? I think the next question should be about autofiction; why are we always making films about ourselves, our own experience?

DC: The truth is that when I’m starting to film, I think that it is not that personal. I convince myself, maybe. But each time I realize what was maybe obvious since the beginning—but I needed the process to realize—which is that I myself was hiding inside a character without even noticing.

For you, it’s different, right? With White Building, it’s so obvious. It is your story.

KN: Yeah, it’s difficult. Obviously it’s about me—not all the parts, some, like the family situation. The character is a bit passive, like me [laughs], and he was a dancer; he was thinking about the future but also trapped by the past. When you set up a shot, you believe in the world you make through the shot. And it’s the same thing when you write the script, you need to believe in it. When you want to make a film, you need to believe in the character; you need to connect with them, with the space… It was difficult for me when I started making fiction films. That was the challenge: how you balance your character and your script with the reality that you have.

DC: I want to ask, what about the desire to archive? Does it exist in this question of autofiction? To what extent do you feel there is a desire to archive the people and the spaces that are part of your life, to keep a trace of these people, even through fiction?.

KN: Yeah, I think in the cinema, you can recreate something, but at the same time you can add something. Maybe now, for me, after making this work, I feel that it’s a bit boring to recreate your life again in cinema. We all can recreate reality in cinema, but cinema can bring us to something other than what we expected as well.

White Building (2021)